7 July 2025, 5-minute read

Notes on Risk-Taking

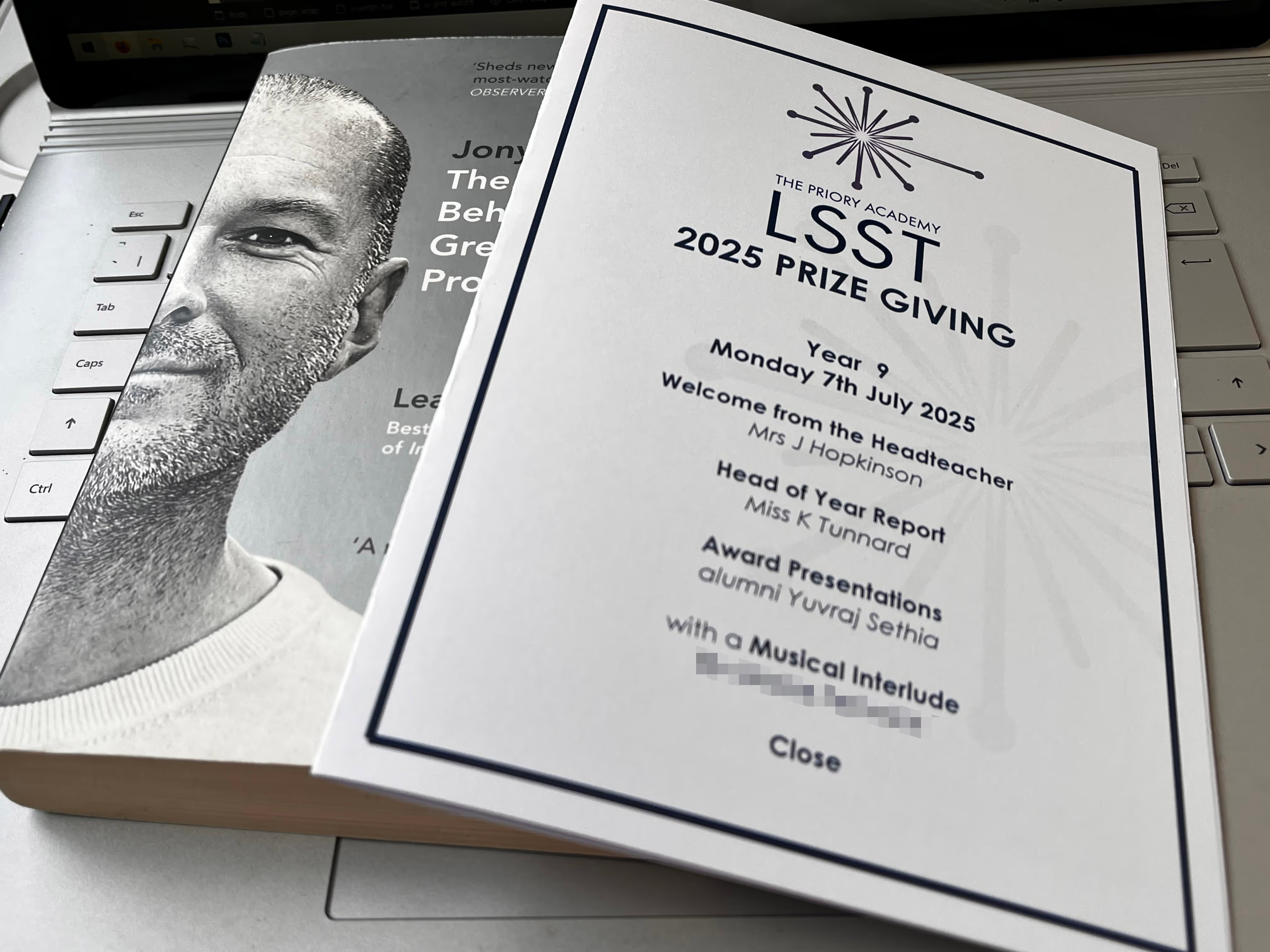

Recently, I was asked to attend my old secondary school, The Priory Academy LSST, to present some prizes to a very talented cohort of Year 9s. Along with this came a challenge: the organisers asked I prepare a five-minute speech sharing some advice that would be valuable to students as they embarked on their GCSE journey.

While the final speech was shortened and simplified, I find this earlier draft belongs here:

It was just a year ago I spoke to you all here about my journey through this school and beyond and about the importance of trusting the process. Today, I’d like to speak a little more in depth about what that process entails.

In my time at Loughborough Design School, the one thing my coursemates and I practiced more than anything was the double-diamond process. It was prescribed to us very early on by one of our user-centred design tutors and in short, it lays out four key stages to solve design problems. For any of you about to embark in D&T studies, this process will become your best friend, even if it will not be formally codified. What I think is most important to recognise, though, is that this process is fundamentally a problem-solving toolkit – one can apply the double-diamond to learn more about and produce better-suited solutions to problems that aren’t solely about making a physical thing. To illustrate this point, I had the good fortune of hearing a renowned actor at the Donmar theatre describe his method for honing in on his portrayal of a character – as he spoke, I realised we were once again greeted by our friend, the double-diamond.

Less talked about, though, is the nebulous mess that comes along with solving any of these problems. So today, I want to share some anecdotes and excerpts from my notebook recently, taken from some of the great designers and visionaries of our time.

One of the most notable designers of this century and a personal source of inspiration, Sir Jony Ive, spoke with Patrick Collison of Stripe in a wonderful fireside interview recently. For any designers and engineers who haven’t seen this talk – you can find it on YouTube and it is well worth a listen.

In his dialogue, Ive brings up the shadowing of measurable product characteristics over intangibles. He says “you would have product conversations - you will end up talking about: schedule, cost, speed, weight, anything where you can generally agree that 6 is a bigger number than 2.” Ive refers to this as an "insidious lie" that "this is all that matters". He argues that the contributions of designers and other creatives, which one often "can't measure easily with a number," are "equally important". These unquantifiable aspects, like making a product "delightful to use and joyful to use," lead to products being used more frequently and can have as much a positive impact as grams and gigahertz.

Ive also speaks about the utmost importance of designing with care. Sometimes, seemingly ‘trivial’ details like the careful management of a cable in product packaging are not about saving seconds or a "trivial utilitarian multiplication and calculation". Instead, they are about creating an experience where (and I have to paraphrase here) the user feels that "somebody gave a STUFF about me". This feeling, he suggests, is a "spiritual thing" and a "way of expressing our gratitude to the species". Solving a functional imperative is not enough – we need to create with care and attention to the human details.

On a similar strand, in his biography of Ive, author Leander Kahney makes mention of Robert Brunner’s approach to industrial design at Apple when pressures mounted from management in 1991. Under increasingly tight timelines, the allowance for design exploration was waning. Brunner had started conducting offline projects – what he called “parallel design investigations”. “The idea was to develop new levels of expression and strategies for handling new technology without the pressure of a deadline”, Brunner explained. Critically, these were kept off the record because it allowed the team to make mistakes, to feel separated enough from the grind of production that the creative juices could percolate. These parallel investigations often ended up producing the best ideas – freed from the immediate functional imperatives, they usually had something cool to point at and say “This is what we can move towards”.

What, I suppose, the key takeaway for you and I is through all of this is the value of asking the seemingly silly questions. Taking on a side quest on a gut feeling because it seems interesting. Taking problem-solving risks on ideas that you know are probably not going to work. Even if it fails (and it may well), what you learn along the way will be invaluable and your end solution will be so much better for it.

Referencing Kahney's biography again: “In a company that was born to innovate, the risk is in not innovating,” Jony said. “The real risk is to think it is safe to play it safe.”

If there’s one thing that I’ve learned separates good designers from great (and in turn, good problem-solvers from great ones), it is this wealth of learning through failing fast and failing often. I will strive to carry this impetus with me going forward and I encourage you to, too. Till the next one!

- Yuvraj