18 May 2025, 5-minute read

Reconciling the Antithesis of Product Design and Anti-Consumerism

Core to the practice of design, I grapple with a silent struggle: the dissonance between my role as a product designer and my personal stance on consumerism. This internal conflict isn't just a fleeting thought but a profound ethical dilemma and I think it is an important one to dedicate some thought to as an ethical designer.

As a product designer, I'm tasked with creating objects of desire: a good product cannot simply be a desiccated, dry functional object – it needs to have some sex appeal. My work is intrinsically tied to the principles of consumerism: generating appeal, driving demand, and ultimately, selling more of whatever the product is. This cycle of capitalist consumption keeps businesses afloat.

However, as someone who firmly harbours anti-consumerist beliefs, this cycle often feels like a betrayal of my values.

Anti-consumerism advocates for minimalism, sustainability, and the reduction of waste. It challenges the very foundation of perpetual growth and excessive consumption that fuels much of the product design industry. Balancing these opposing forces requires constant introspection and often, a redefinition of what it means to be a responsible designer.

The key to reconciling this dissonance lies in shifting my perspective on success and responsibility. Traditional metrics of success in product design often revolve around sales figures, market penetration, and consumer engagement. However, as an anti-consumerist designer, I find solace in redefining success through the lens of sustainability, longevity, and ethical impact.

Sustainability needs to built-in as a core pillar of moral product design. For instance, when designing the CityMax Pro, I focused on incorporating sustainable materials and energy-efficient features. CityMax Pro is formed from cast aluminium as opposed to traditional subtractive CNC milling (which is a rather wasteful process). Its entire premise and function is also rooted in the idea of reducing power consumption to only the bare necessity; it only lights up areas in use by pedestrians - this serves to reduce its carbon footprint. This approach not only makes the product environmentally friendly but also aligns with my values by promoting longevity and reducing the need for frequent replacements.

Next in the list of key principles is longevity: shit needs to last and if it fails: a) it should fail gracefully and b) there should be a low-effort route to reinstating the product’s service. All of the projects I worked on at Loughborough and since have been extremely easy to repair, featuring easy disassembly procedures and an almost pedantic focus on modularity. In my design of the Field Spot, I prioritised durability and repairability: the product is internally reinforced and has thick walls so it can hold up to the harsh demands of contact sports. Inside, Field Spot uses standard screws and modular components for quick and easy repairs. The battery is connected with clip-on ‘Lego-style’ connectors and held in place with a strap.

A common misconception that rubs me the wrong way is that repairability and finesse cannot co-exist, as if they are the Oggy and the Cockroaches of product design. The reality could not be farther from the truth – sure, implementing repair-friendly features requires extra thought and imposes further constraints on the solution space of a design challenge. Yet we have seen careful engineering overcome these, time and time again. Take Apple’s most recent iteration of MacBook Pro (please lower your pitchfork – I will highlight Apple’s many sins against repairability later in this post and likely many a time in the future). Regarded as one of the highest-quality fit-and-finish laptops you can buy, the internals reveal the ports are modular and can be changed independent of each other and the logic board (in theory!). Of course for every point Apple gets for modularity, they lose two for their abhorrent crimes against repair in the form of ‘parts pairing’ (also known as serialisation).

An essential aspect of aligning my work with anti-consumerist values is rejecting planned obsolescence and the temptation to choose the cheapest manufacturing methods and materials. Planned obsolescence: the practice of designing products with a limited lifespan to encourage repeated purchases, is antithetical to sustainability and ethical design. By rejecting this practice, I commit to creating products that are built to last, reducing waste and promoting long-term use.

Choosing the cheapest manufacturing methods and materials often compromises the quality and durability of a product. This not only undermines the product's longevity but also contributes to a culture of disposable goods. For instance, in the design of the Coffee Machine, I avoided rock-bottom components in favour of materials that enhance durability and repairability. This approach ensures that the product remains functional and desirable for years, rather than becoming obsolete and discarded.

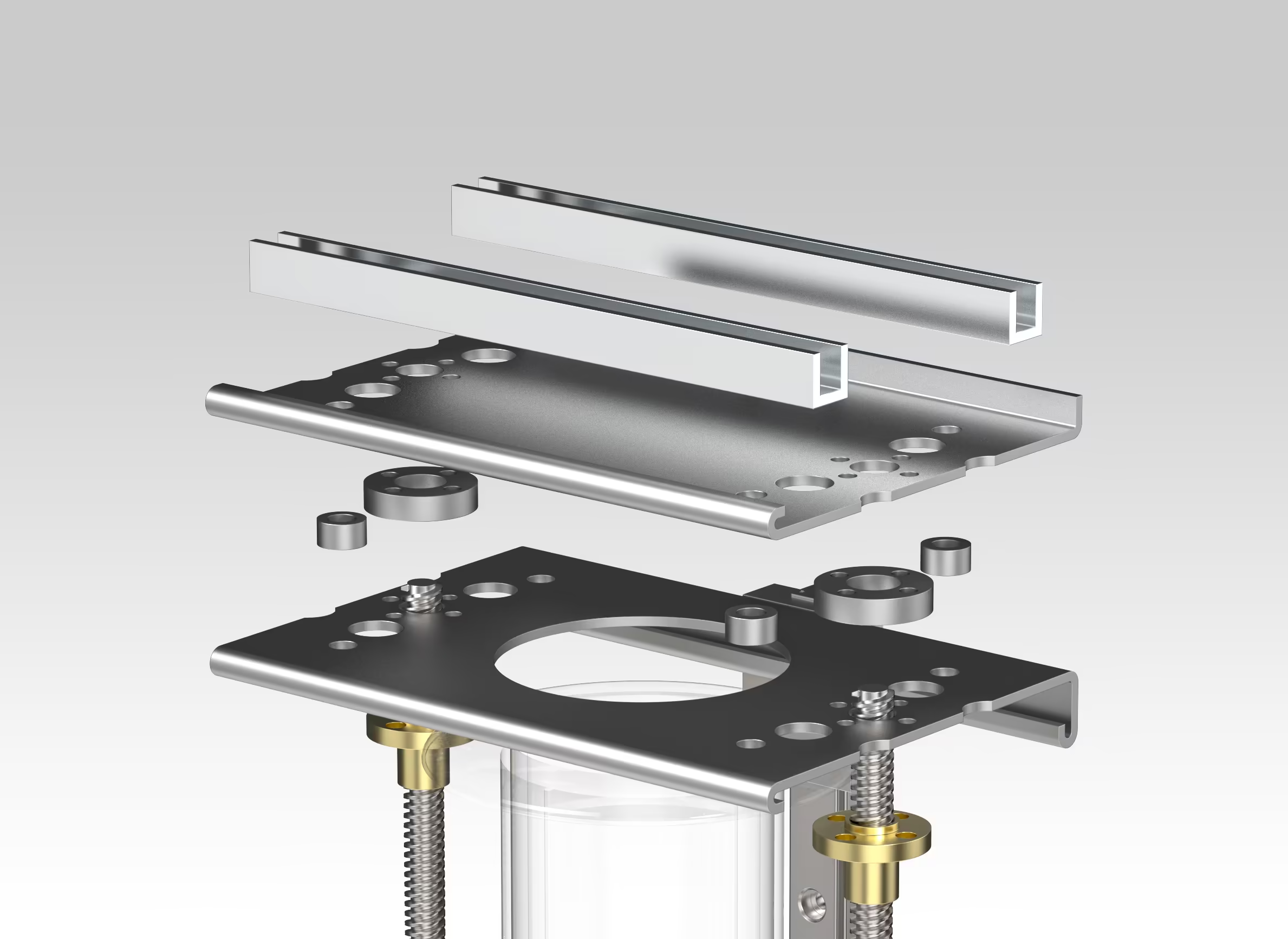

When designing the STRXCT N1 Microserver, I vowed to avoid single-use plastics in the packaging of the product. This was far easier said than done: initially I planned on using a clever technique of paper pulp molding to create packaging inserts. After a string of failures and delays caused by the exploration of implementing this technique, it became clear it would not be feasible (maybe sometime down the road, pulp inserts!). I turned to 3D printing TPU inserts – which worked a charm, but broke my rule of avoiding single-use plastics. It turned out, the answer was staring me right in the face – hexagonal paper provided a flexible, sustainable (and very affordable) way of protecting the internals of the box. As such, the only plastic you’ll find in or on the STRXCT N1 box is the actual case parts (the production of which were only made possible by FFF 3D printing). As a side note, I’d love to do a behind-the-scenes on the year-long design process of the N1 at some point. Maybe that will materialise here or on YouTube.

The journey to reconcile the dissonance between being a product designer and being anti-consumerism is deeply personal and ongoing. It requires me to constantly evaluate my choices, advocate for ethical practices within my industry, and strive to create products that do more good than harm.

I hope this nebulous collection of thoughts provides some value to you – the distillation of which is left as an exercise to the reader! Till the next one.

- Yuvraj