2 August 2025, 7-minute read

For Love of the Art

“When you make something with love and with care, even though the people that you've made it for - you don't know their story, they don't know your story; you'll never even shake their hands. But when they use the product that you've made it it's a way (…) of expressing our gratitude to the species.”

I think about these words a lot. In his interview with Patrick Collison (which I have written about previously), Jony Ive speaks about how one can sense care in a product (and just as well sense carelessness). Whether or not we are conscious of this, I believe this is true at some level.

In our daily lives, we experience well-designed and poorly designed objects, systems, and processes. One may be fooled into thinking that there is a third alternative, but choosing not to engage with the design challenge is a design decision in itself – one that only increases the likelihood of a poorer result. In other words, there is no such thing as an undesigned product.

In my final year of studies at Loughborough Design School, the entire cohort (BA and BSc students) takes part in a mandatory live project. Studies and assignments from all other modules are suspended and everyone is expected to devote all their attention to this project. You can read more about Live Projects at LDS in this post I wrote at the time.

The brief I picked was set by Holophane Europe Ltd in association with the Lighting Industry Association and I set about designing what would eventually become CityMax Pro. The deliverable was simple - three boards as follows:

A research board containing a summary of research undertaken and contextualising the final solution

A situation board, graphically walking the reader through the use case for the product through storyboard format

A hero render board showcasing the product in its fully glory and some key features of the product

My product, CityMax Pro, was designed to be a lighting solution that implemented selective beam technology to reduce light pollution (and thus wildlife impact) at the urban perimeter. It’s powered by six IR vision cameras, a 103-LED light array, and a prismatic collimator that leverages Holophane’s infamous capability in prismatic glass lens manufacturing – all wrapped in a sleek and repair-friendly aluminium and glass design.

CityMax Pro - Urban Perimeter Lighting Reimagined

Product internals weren’t explicitly mentioned in the deliverable requirements but to design a product in the final year without designing the insides at some level would be heresy. While all of the internals of CityMax Pro weren’t considered (the timeframe didn’t allow for modelling things like internal fastenings, cables, DfM/DfA etc), I felt it was right to build out the main internal components.

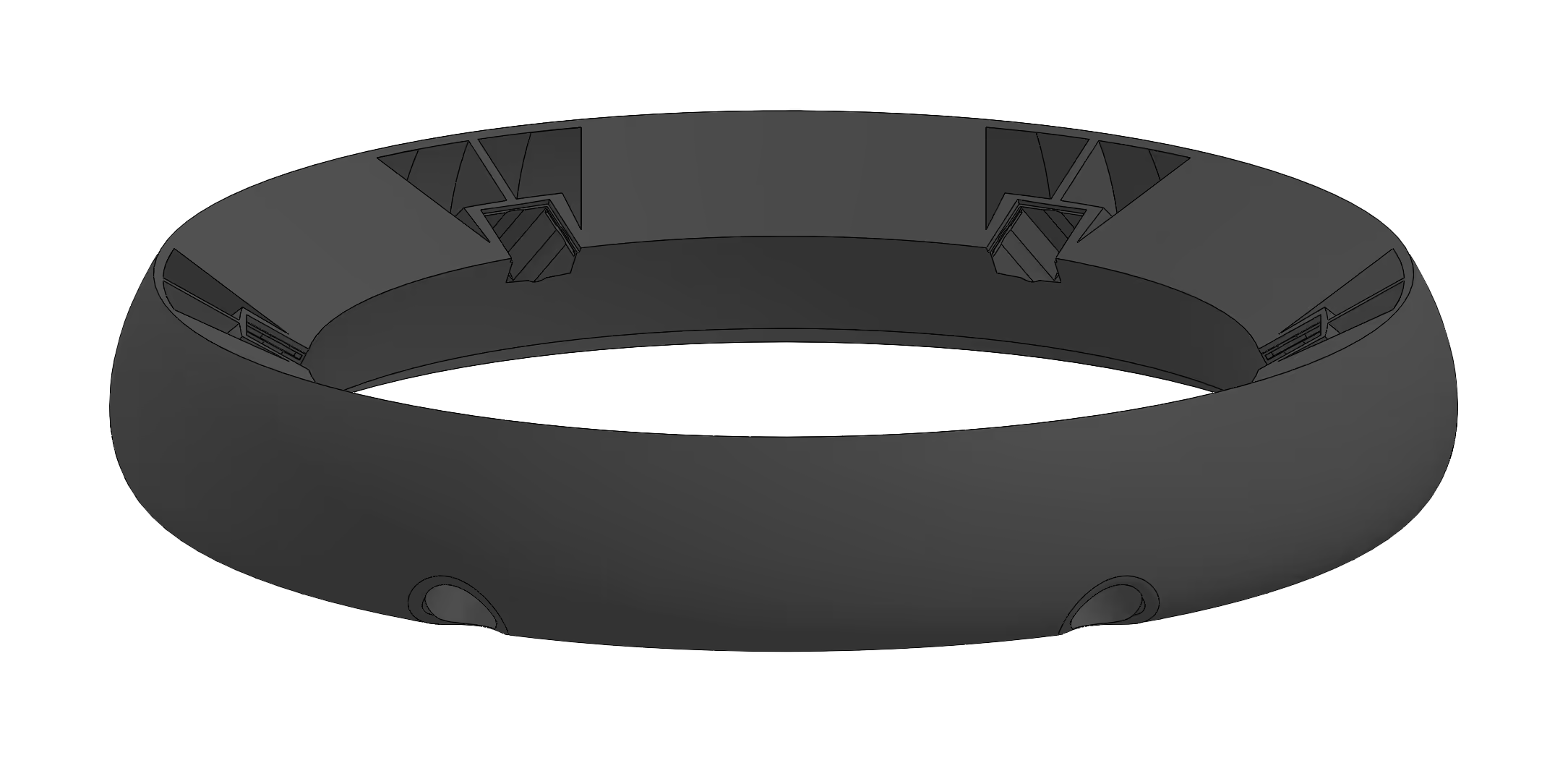

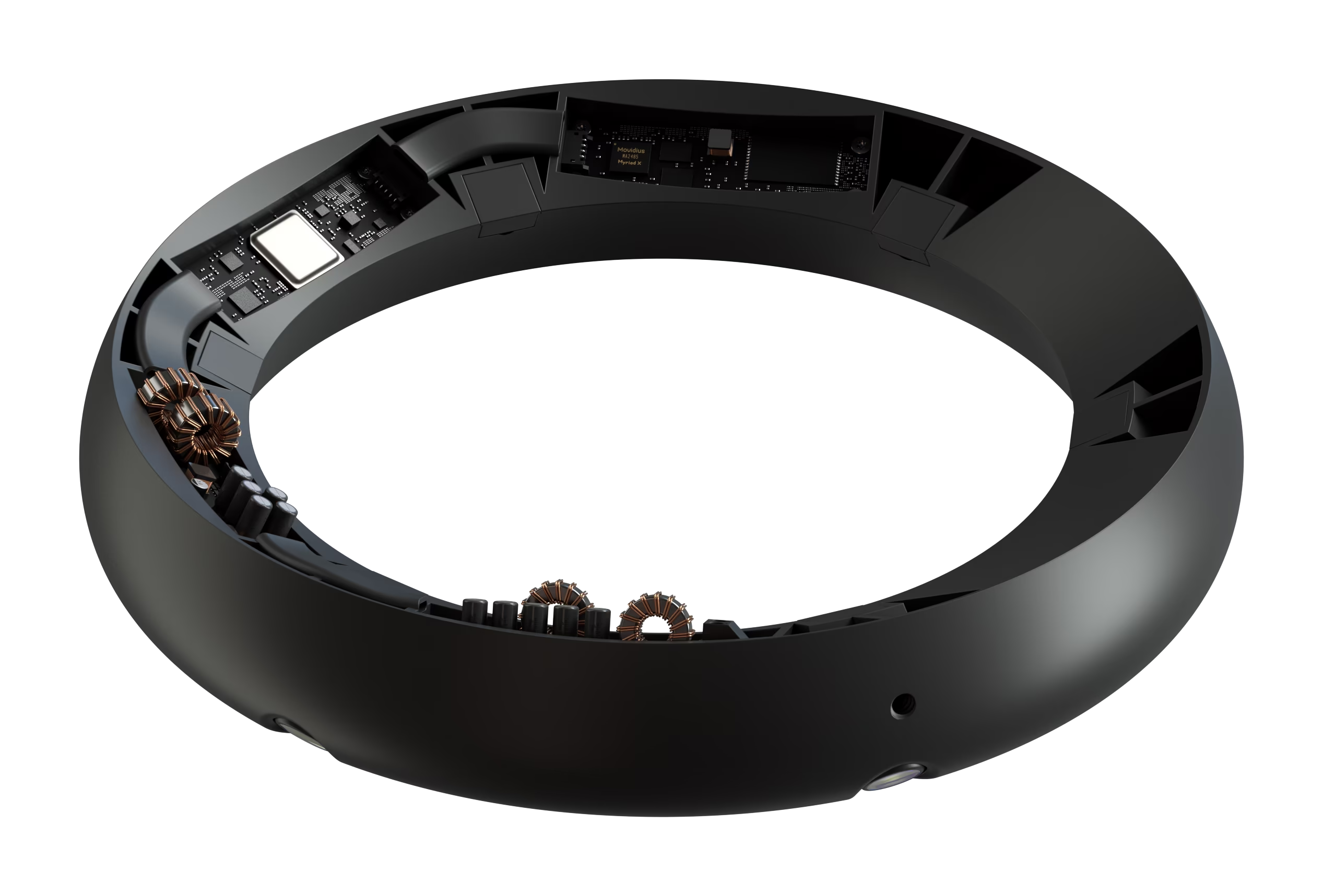

To keep the spatial and material requirements to a minimum, the electronic and power components of the luminaire were arranged in a toroidal case that surrounded the diffusor lens. I referred to this in my internal files as the ring assembly. This assembly consisted of a round ABS case with cavities for all of the components, like the IR cameras and the other electronics.

The ring assembly before making cavities for the PCBs.

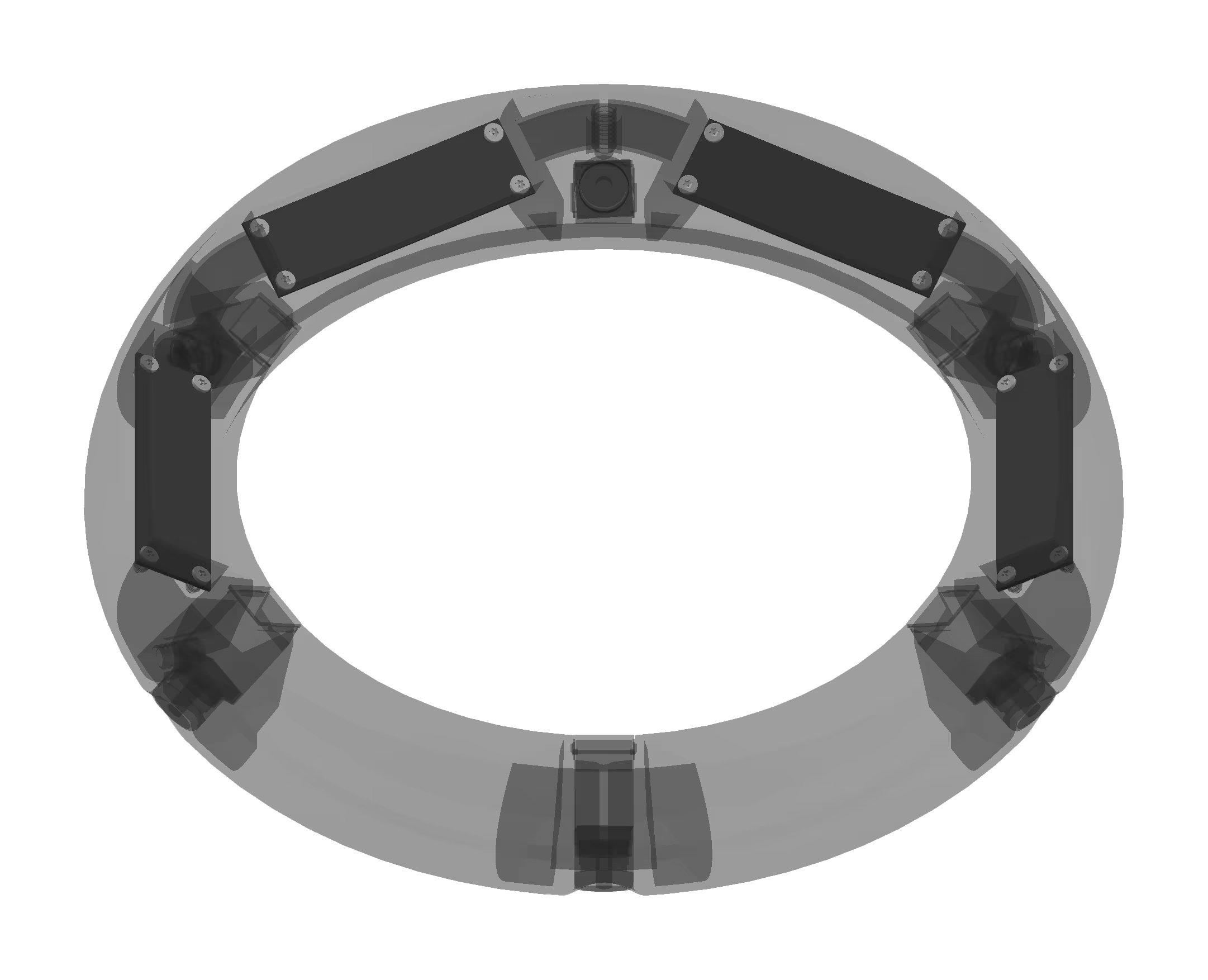

The ring assembly presented a unique challenge when it came to putting the electronics inside: there simply wasn’t enough room for a full-size PCB that could contain all of the electronic components the luminaire needed. Keep in mind that the PSU needed to power up to 100W of peak output for the luminaire alone with a few more to power the vision system and projection processor. The solution was to split the PCB into four separate boards and space them out radially around the toroidal case. This ended up being better regardless as now the power PCB was isolated from the processor PCBs and the thermal design of the system could be catered to each board’s needs (something that wasn’t explored in the scope of the submission).

With the optical components fully designed and laid out, CAD models for the Sony IR sensors acquired, and the toroidal case also modelled with tolerance cavities for the sensors, it would have been enough to model four green cuboids, call them PCBs, and take the model into C4D for texturing. It was 02:00 on the day before submission; with the other two boards complete, I could have called it a night and had ample time to make the hero and internal renders and assemble the third board.

The PCBs as unpopulated cuboids. The rest of the ring assembly is show in translucency.

Creatives from all disciplines will no doubt relate to what I felt next. Given the level of endorsement of the optical half of the components, it seemed incongruent to have such barebones models for the PCBs.

Of course it wasn’t enough to simply model empty green panels! The electronic components were integral to the functionality of CityMax Pro.

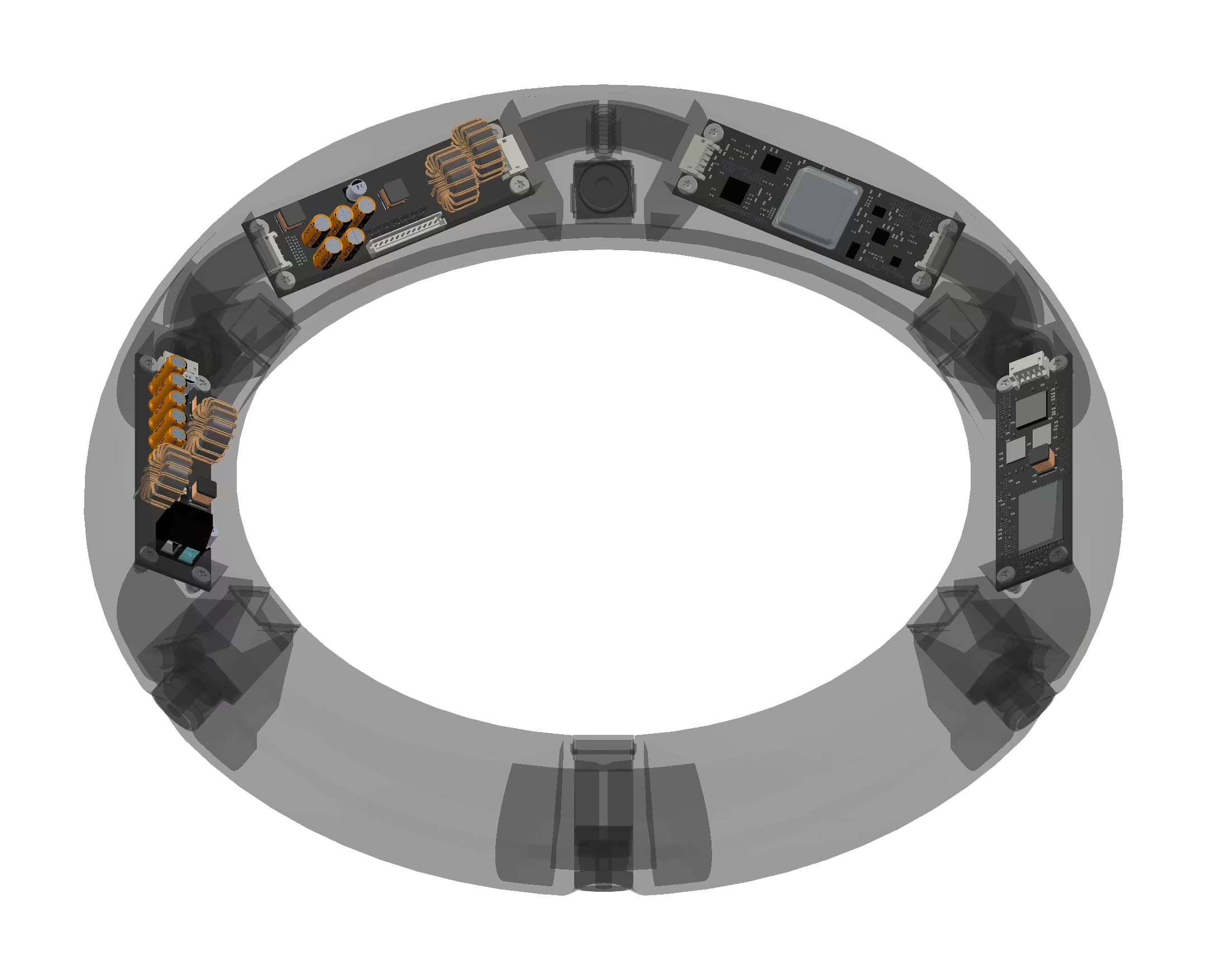

Whether or not the components I placed were canonical to the final story of the luminaire, I firmly believed the boards needed populating in a way that is typical of high-density electronics boards. I could perhaps try and spin reasons as to why this was the right thing to do from a logical viewpoint, but the root reason was none other than for love of the art.

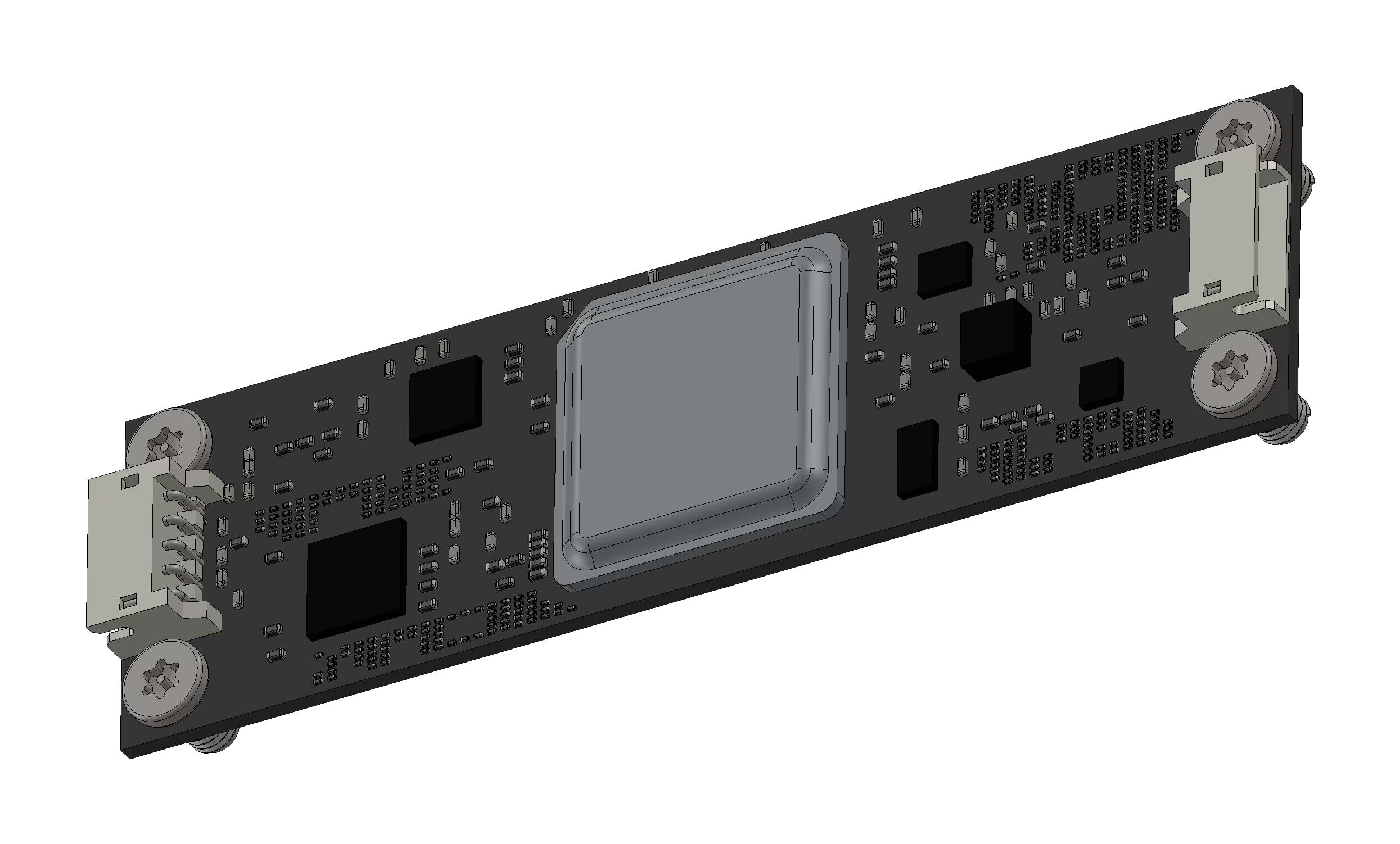

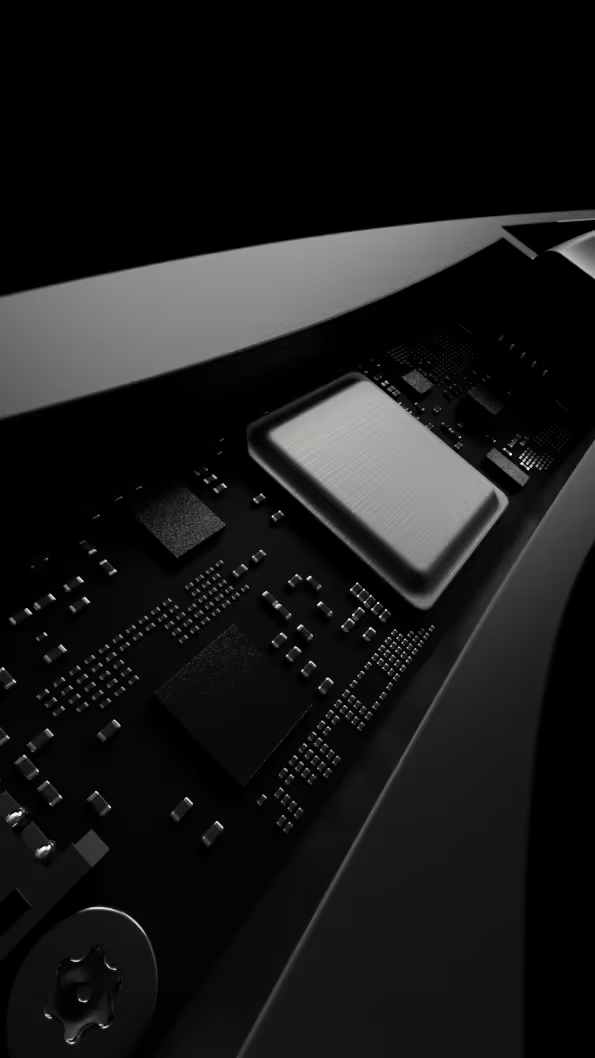

I spent the next five hours making and placing models of PTH and SMD PCB components, including various sizes of SMD capacitors and resistors, the Intel machine vision chip, and an unspecified shielded processor package. Studying high-density PCBs and drawing on my own familiarity, I placed arrays of components in a somewhat archetypical manner. Was the effort (and sleep deprivation) worth it? If one only considers the mark increase against the extra hours spent the answer is unequivocally ‘no’.

The PCBs after populating with components. The rest of the ring assembly is show in translucency.

One of the populated PCBs in SolidWorks

An early PCB render

But looking at the renders, I hope you’ll agree that there is a night-and-day difference, and this extra care and attention is what people pick up on subconsciously – or so I firmly believe. Four green rectangles may have sufficed for Holophane’s judging process, but I hoped that when they saw the physics-accurate prismatic lens, or the archetypically populated PCBs which were colour-matched to the other parts in the ring assembly that the judges would feel the same sense of care and attention to detail. Harkening back to Ive’s words from the start of this post: it’s the little things that matter – the ones that don’t serve some functional, empirical imperative but rather communicate to the people we’ve made something for that we care about them.

The final ring assembly, rendered

I’m not entirely sure how the mechanics of this mental response play out. I am entirely unqualified in both psychology and philosophy, after all. I hypothesise that we subconsciously understand and expect products to be made consistently inside and out. So when the parts we can see are designed with care and attention to detail, I think we are pre-programmed to assume (with no other context) that the parts we cannot see are congruent with these qualities.

Making anything is a balancing act – rather crudely put, a compromise between care, speed, and intensity. One can work very intensely to put something out with great attention to detail in a shorter timeframe. One can put work out in a shorter timeframe working at normal intensity but skimping on the qualities discussed above. Or for those who are afforded the liberty, one can build something designed with great care in a longer timeframe at usual intensity. This is something Ive is asked about by Collison and his response provides great insight into the recipe for design success that the Apple Industrial Design Group is renown for.

There exist countless examples well-designed products in the world: OXO’s Good Grips peeler, the TfL London integrated transport system, and maybe most prolific although underappreciated: the BIC Cristal to name a few. A common characteristic is that of immaculate care and focus on the user even if the result cannot be measured by quantitative metrics. Sometimes we don’t endorse these design details for rational reasons, rather there is a deeper reverence for creation at play: it's for love of the art.

Till the next one,

- Yuvraj

CityMax ® and The Holophane Logomark are registered trademarks of Holophane Europe Ltd.